poetry & criticism

Elizabeth Kate Switaj has worked at the College of the Marshall Islands in the Central Pacific since 2013. She holds a PhD in English from Queen’s University Belfast, an MFA in Poetics & Creative Writing from New College of California, a BA from The Evergreen State College, and an AAS from Bellevue College.

Serial Experiments

- Chapbook

- Forthcoming from Alien Buddha Press

The Articulations

- Published November 12, 2024 by Kernpunkt Press

- Found language sequence exploring conceptions of the body

- Part of a tête-bêche with Amelia K’s Amouroboros

Supply Chain Problems

- Mini-Chapbook

- Read for free from Ghost City Press

The Bringers of Fruit: An Oratorio

- Polyvocalic retelling of the Persephone myth

- Available from 11:11 Press

- Winner of the 2023 Whirling Prize

- Discussed in Looking Back at Full Stop

James Joyce’s Teaching Life and Methods

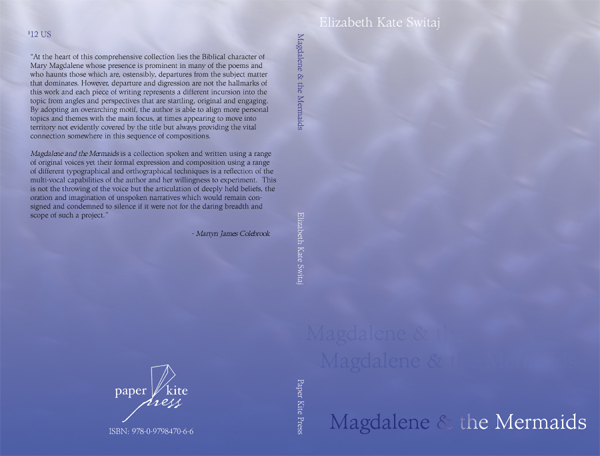

Magdalene & the Mermaids

- Mythic poetry published by Paper Kite Press

- Available via HathiTrust

- Reviewed at Everything Distils into Reading

The Broken Sanctuary

- Chapbook of ecopoetry

- Published by Ypolita Press